|

The lure of a miracle pill for mental

illness

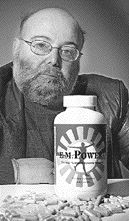

Empowerplus has been banned from Canada, but

some users swear it's given them mental wellness without drugs.

Joanne Laucius reports.

Monday, July 21, 2003

In September 2001, Caro Overdulve told his parents he wanted to drop his schizophrenia medications and take a vitamin and mineral supplement from an Alberta company called Truehope. The company promised its Empowerplus supplement would bring mental wellness without drugs. Caro was sold. But the decision was the start of a downward spiral, says his mother, Anne Overdulve. In the two years since, Caro, now 32, has descended into psychosis and been charged with assault, mischief and criminal harassment. He is still in jail and will appear in court today. On June 6, Health Canada issued a health advisory about Empowerplus, saying users could be putting their health at risk with an unproved drug. Health Canada has blocked Empowerplus, which is manufactured in the U.S., from coming into Canada. Last week, Health Canada officials and RCMP experts in computer retrieval raided the offices of Truehope Nutritional Support Limited in Raymond, Alta., scooping up computer and paper files and shutting down the call centre. Phone calls and e-mails poured into the Alberta division of the Canadian Mental Health Association, where executive director Ron Lajeunesse warned that mental patients may kill themselves over the issue -- and he knew of two deaths already. Truehope's co-founder, David Hardy, calls the supplement "the most significant breakthrough in health since time's beginning." Health Canada calls Empowerplus a "drug." Mr. Hardy calls it "the nutrients." Health Canada says users must be protected. Truehope says it will sue Health Canada for a "discriminatory attack against the mentally ill." Blocking Empowerplus's entry into Canada has set off a chorus of anger from Truehope customers who claim the supplement has kept them from the brink of suicide and saved them from the psych ward. "Health Canada is trying to make us sound like criminals," said Mr. Hardy. But others besides Health Canada have concerns. Some fear the promise of a miracle cure is even more dangerous to a vulnerable group of people. Sheila Deighton, executive director of the Ottawa-Carleton chapter of the Schizophrenia Society of Ontario, is concerned about schizophrenia patients who drop their medications in favour of Empowerplus. "They believe that all they need is this vitamin treatment. But once they stop their meds, the bizarre behaviour returns," she said. "It's like a diabetic who is told they don't need insulin." --- The Truehope story has all the elements of a dramatic medical breakthrough story: A serendipitous discovery, a miracle cure, a David-and-Goliath battle between two feisty independents who want to help the struggling and an unfeeling government bureaucracy. The story, which stretches back more than seven years, starts like this: Two men with no medical backgrounds, plagued by tragic family histories of mental illness, try an unorthodox treatment in a bid to prevent more suicides and illness in their families. One of the pair, Mr. Hardy, had experience in animal nutrition and mentions a feed supplement used to prevent aggressive pigs from savaging each other in their pens to his friend Anthony Stephan. The two produce a human version of the feed supplement. They give it to the children and it works. Mr. Stephan's daughter, Autumn Stringam, had bipolar disorder, a mood roller coaster that goes from the highest highs to the deepest depressions. She said she went from being fat, depressed and in a wheelchair to living a normal life, free of pharmaceuticals. Then, three years ago, Truehope made headlines again, this time when a University of Calgary researcher released a small study that concluded the supplement had some success in treating people with bipolar disorder. "For some patients, the supplement has entirely replaced their psychotropic medications and they have remained well," researcher Bonnie Kaplan told the Calgary Herald. In September 2001, Mr. Hardy and Mr. Stephan were honoured at an award dinner named after Margot Kidder, the Canadian Superman actress who claims she overcame mental health problems through alternative treatments. That same month, Caro Overdulve started taking Empowerplus. Mr. Overdulve was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the spring of 1993, just weeks after he graduated from Wilfrid Laurier University and began to behave very oddly, staging temper tantrums on the floor of his parents' home and wandering naked, said Anne Overdulve. Drugs helped to control his symptoms, but Mr. Overdulve told his parents the drugs were making him gain weight and were giving him insomnia. The doctors weren't listening, he complained. He paid for the first few months of Empowerplus himself, selling his used Chevrolet Cavalier to pay. His parents were skeptical, but willing to try anything that might help their son. They agreed to foot the rest of the bill, arranging for automatic credit card deductions for the pills. From November to February, they were billed six times, for a total of more than $1,600. In March 2002, they were charged $1,248 for an additional six-month supply of the pills. But the Overdulves found their son's supplements weren't working. Worse, his behaviour was getting increasingly bizarre and even alarming. When they went to visit him in a townhouse they owned in Barrhaven, they found the place filthy. Pots with the charred remains of food were piled in the sink. Drinking glasses and mugs containing liquids were floating islands of mould, recalls Mrs. Overdulve. Mr. Overdulve was taking 32 capsules a day, but he was eating them by the handful. Often, he missed his mouth, scattering capsules everywhere. The Overdulves found that their son had racked up $600 on his phone bill for calls to a Truehope support line in Orléans, even though the centre had a toll-free line. The Overdulves refused to buy more of the supplement. And their son slipped away from them. Between July 2002 and last April, Mr. Overdulve lived in a string of apartments, rooming houses and homeless shelters. He was hospitalized three times, in one instance returning to his schizophrenia medications, then dropping them again. He accused his father of working for the Mafia and threatened his newborn nephew, said his mother. "Every time he stops the meds, he relapses," said Mrs. Overdulve. At the end of April, Mr. Overdulve got an apartment in Nepean and asked his parents to co-sign. His family hoped he had turned things around. Three weeks later, he was charged with assault, mischief and criminal harassment after a man in the apartment building reported he had been struck and obscenities were carved into the door of his apartment. Truehope has driven a wedge between the Overdulves and their son, said Mrs. Overdulve. "He listens to them, not to us. There is no getting beyond it," she said. "Anyone who knew him before doesn't even recognize him now." Still, others say Empowerplus has done what pharmaceuticals could not do. Jane Callen's daughter, Leah, now a 19-year-old music student at the University of Ottawa, was diagnosed nine years ago with bipolar disorder. Ms. Callen's psychiatrist had her taking eight different psychotropic drugs at once -- "a chemical cocktail." The drugs put Ms. Callen into a stupor, but did not alleviate the symptoms. About two years ago, her family doctor learned two of her other patients were taking the supplement. Ms. Callen's mother says the doctor suggested them to Ms. Callen, and the psychiatrist went along. (Neither doctor would be interviewed for this story.) "It was incredible. She started doing so much better," Mrs. Callen said. Ms. Callen has been able to volunteer, to get back singing and join a writer's group. "Normally she's either suicidally depressed for months on end, and then psychotic, and then suicidal, so there's no relief in her life. Well the minerals have taken away all the depressive side of the illness. It just removed them," said Mrs. Callen. "In the meantime her psychiatrist monitors her, and if she gets a manic phase -- and it doesn't cover that; I wouldn't want to pretend it's a cure-all -- he looks after those symptoms. And when they agree she's over that, she goes back on the minerals." "Everyone agrees this is the best Leah can get. ... Medication alone just doesn't do it." --- The excitement about Truehope really took off after Dr. Kaplan, a psychologist at the Alberta Children's Hospital who teaches on the University of Calgary's medical faculty, wrote an article published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry saying that 11 bipolar patients who took the mixture of vitamins and nutrients reported feeling a new kind of effect from the mineral supplement. Instead of feeling their bipolar symptoms were suppressed or masked, as with psychotropic drugs, they felt "normal," wrote Dr. Kaplan, who presented her early results at two psychiatric conferences. All the patients who were taking psychotropic drugs were able to cut their medication by more than half while taking the mineral pills. But why should simple minerals work at all? Because trace metals and minerals are already widely implicated in mental heath, Dr. Kaplan wrote. Zinc, calcium, copper, iron and magnesium all help neurons to work effectively, and the lack of them may cause behavioural abnormality. And one of the main drugs used to treat abnormal behaviour -- lithium -- is itself a metal. And while the study does nothing to tell which of the 36 minerals may be "the important one," she added, "we would say that the likelihood of finding a single effective ingredient is very small." She floated the theory that a broad-based set of minerals may be more useful than single ingredients. A lot of people were curious about the discovery, including Marvin Ross, a medical writer who is now the president of the Hamilton chapter of the Schizophrenia Society of Ontario. Mr. Ross was puzzled why people with no medical training were recommending the supplement to people with serious psychiatric disorders. And he was alarmed that Dr. Kaplan's study was being taken as proof that it worked. "An open label trial of short duration is not definitive proof," said Mr. Ross, who has since co-written an online book called Pig Pills Inc: The Anatomy of an Academic and Alternative Health Fraud. In the U.S., others were also watching online as both testimonials and denunciations of the supplement popped up on the Internet. Elizabeth Woeckner, a board member of Citizens for Responsible Care and Research, an organization concerned about the protection of human subjects in research, wondered why the product was being tested on human subjects if it hadn't been approved by Health Canada. And why if, as Truehope claimed, the 36 vitamins, minerals and nutrients in the pills could be found in any drugstore, did the research have to use Truehope's proprietary formula? She even questioned the pig supplement connection. "Ear and tail biting syndrome in pigs no more resembles mania or hypomania than I can fly," she said. Since going public, Dr. Kaplan has been accused of "quackery" and promoting "pig pills." Further research into the supplement has been halted by Health Canada. She has since backed away from the debate, and wouldn't be interviewed for this article. "The University of Calgary research has been very promising. While the participants in our research generally benefited mentally and remained healthy physically, the results are preliminary," she said in a written statement. "Case series published by two independent clinicians in the U.S. have replicated these findings." In a radio interview, Dr. Kaplan said it's reasonable to learn from pigs: "You know this is not that unusual. We are used to a lot of human health-related things being tested on lab animals, but what we are not is some insight coming from farm animals." Others in the mental health field are also willing to give the supplement a try. Ottawa psychiatrist Dr. Ruth Biggar said it isn't her first line of defence, but it works for some patients very well -- and for others not at all. Others show partial improvement. "A couple of people have tried everything out there and have not tolerated it. It's not like we have a lot to fall back on." Mood swings can be linked to nutritional deficiency, said Dr. Biggar, who has about four patients who use the supplement. "We don't know what vital component of the Empower is working," she said. But she notes that it tends to be more effective for people with bipolar disorder. "It's not a cross-the-board kind of nutritional supplement," she said. If a patient asked to try it, she would consider adding it to the medication regimen and gradually reducing meds. But she warns that schizophrenic patients have impaired judgment. "Anyone who is doing this needs to be followed by a psychiatrist or doctor," she said. "You don't just go off your meds." Meanwhile, Truehope has claimed that the supplements are effective for schizophrenia and a lot more -- attention deficit disorder, autism, Tourette syndrome, fibromyalgia, panic attacks and even brain injuries. Serious disorders like these should not be self-medicated or self-diagnosed, Health Canada said in a statement. Tara Madigan, a spokeswoman for Health Canada, said it is Truehope's responsibility to provide Health Canada with data that would support the therapeutic claims being promoted for the drug. Dr. Kaplan's studies were exploratory in nature and involved only a small number of subjects, she said. Fourteen subjects were enrolled in, but only 11 completed, the six-month trial in 2001. Another 2002 study involved case reports on the use of Empower on two children, eight and 12 years of age. Even the researchers acknowledge there were many weaknesses in the design of the two studies, said Ms. Madigan. For one thing, there was no placebo control. Another potential source of bias is from the psychiatrists themselves. "As in any open-label study, unblinded assessments can result in exaggerated results," she said. Vitamin toxicity is also a serious consideration. As well, there is the problem of how the supplement interacts with medications, she said. Mr. Hardy insists there are no health risks associated with the supplement. "You don't have to be a rocket scientist to know that every product in the blend has been in use at least for 40 years," he said. As for patients who go off their meds, mentally ill people who take pharmaceutical drugs have a chemical imbalance, he maintains. There may be disturbances when the brain is normalized by using the supplement, he said. "The best success happens when people slowly transition from their medications." Still, there are many questions about how Truehope runs its operations. Mr. Hardy says he and Mr. Stephan "don't make a dime" from the supplement. However, if a customer takes 18 pills a day, it costs about $165 a month to buy Empowerplus. If the company has 3,000 customers in Canada alone, it's making almost $500,000 a month. Mr. Stephan insists that figure is incorrect, because so many customers get their supplements for free. It's more like $300,000 and a lot of the money goes to pay the 55 "support" workers who operate the phones. Many have themselves suffered from mental illnesses. The fact that they have no medical credentials concerns people like Mr. Ross. "People have the right to try whatever they want," he said. "But they should work with their doctors." Mr. Hardy says Truehope customers can get more personal time with a "support" worker than a busy doctor. And, adds Mr.Stephan, people who have had mental problems "know what works and what doesn't work. "All we're here to do is tell you how the program operates." Empowerplus doesn't work for everyone, said Mr. Stephan. Anything could tip the balance of a mentally ill person -- not taking enough of the supplement, an illness or stress. "But they come back for more. Because they felt better on the nutrients," he said. Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, a well-known research psychiatrist who is executive director of the Stanley Medical Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, says his institute is considering doing a "careful" double-blind study of the supplement. The product still needs U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in order for that to happen, however. "Our belief is that there is sufficient anecdotal information that warrants careful study," he said. "It tells you that it's worth looking at, one way or another." But anecdotal studies don't wash in the greater scheme of things he said. He wouldn't recommend this kind of treatment to a patient. "No. Wait for there to be hard data," he said. "Any time a patient goes off their mediations, they are likely to have a relapse." He's also concerned about the fact that Truehope claims to be effective for a wide variety of disorders. "In the more than 30 years I have been studying mental illnesses, there have always been some people who have made a good living treating people with schizophrenia with various vitamin mixtures," said Dr. Torrey. "If it works, use it. But the amount of hard research in this area is very, very small." Much more proof is needed, says Dr. Jacques Bradwejn, psychiatrist-in-chief of the Royal Ottawa Hospital. "It's the whole question of showing efficacy through standards of research that include clinical trials," he said. That means the supplement needs to go through a test against a placebo. Yes, the rules are strict and will take years to follow, but "the same approach needs to be taken for any products that have claims (of medical effectiveness) attached to them," he said. As well, the manufacturers need to prove their mix is standardized and pure, he said. In the past, some herbal remedies have run into problems with doses that fluctuate or background chemicals that creep in unnoticed and do harm. Mr. Hardy and Mr. Stephan have questions of their own: Why not let more studies go ahead? "We feel we're onto something, and it has to be looked into," said Mr. Stephan. "If they think it's a scam, then let's prove it." © Copyright

2003 The Ottawa Citizen | |||||||||||||||||||||